We can draw parallels in the stages through which software projects and children tend to progress.

This week, one of my kids turned 18, and is therefore an adult – at least in the eyes of law in the UK, where we live. This is scary. For me, and probably for the rest of the UK.

It also got me thinking about how there are similarities between the development lifecycle for software and kids, and that we can probably draw some parallels in the stages through which they tend to progress. Here are the ones that occurred to me.

1. Creation

Creating a new software project is very easy, and a relatively quick process, though sometimes you have a huge number of false starts and things don’t go as planned. The same, it turns out, applies when creating children. Another similarity is that many software projects are created by people who don’t really know what they’re doing, and shouldn’t be allowed anywhere near the process at all. Equally useless at the process are people who have only a theoretical understanding of how it should work, having studied it at school, college or university, but who feel that they are perfectly qualified.

The people who are best qualified – those who have done it before – are either rather blasé about it and go about creating new ones all over the place, or are so damaged by it all that they swear they’ll never do it again. Beware: there are also numerous incidents of people starting software processes at very young ages, or when they had no intention of doing so.

2. Naming

Naming a software project – or a baby – is an important step, as it’s notoriously difficult to change once you’ve assigned a name. While there’s always a temptation to create a “clever” or “funny” name for your project, or come up with an alternative spelling of a well-known word, you creation will suffer if you allow yourself to be so tempted. Use of non-ASCII characters will either be considered silly, or, for non-Anglophone names, lead to complications when your project (or child) is exposed to other cultures.

3. Ownership

When you create a software project, you need to be careful that your employer (or educational establishment) doesn’t lay claim to it. This is rarely a problem for human progeny (if it is, you really need to check your employment contract), but issues can arise when two contributors are involved and wish to go their separate ways, or if other contributors – e.g. mothers-in-law – feel that their input should have more recognition, and expect more of their commits to be merged into main.

4. Language choice

The choice of language may be constrained by the main contributors’ expertise, but support for multiple languages can be very beneficial to a project or child. Be aware that confusion can occur, particularly at early stages, and it is generally worthwhile trying to avoid contributors attempting to use languages in which they are not fluent.

5. Documentation

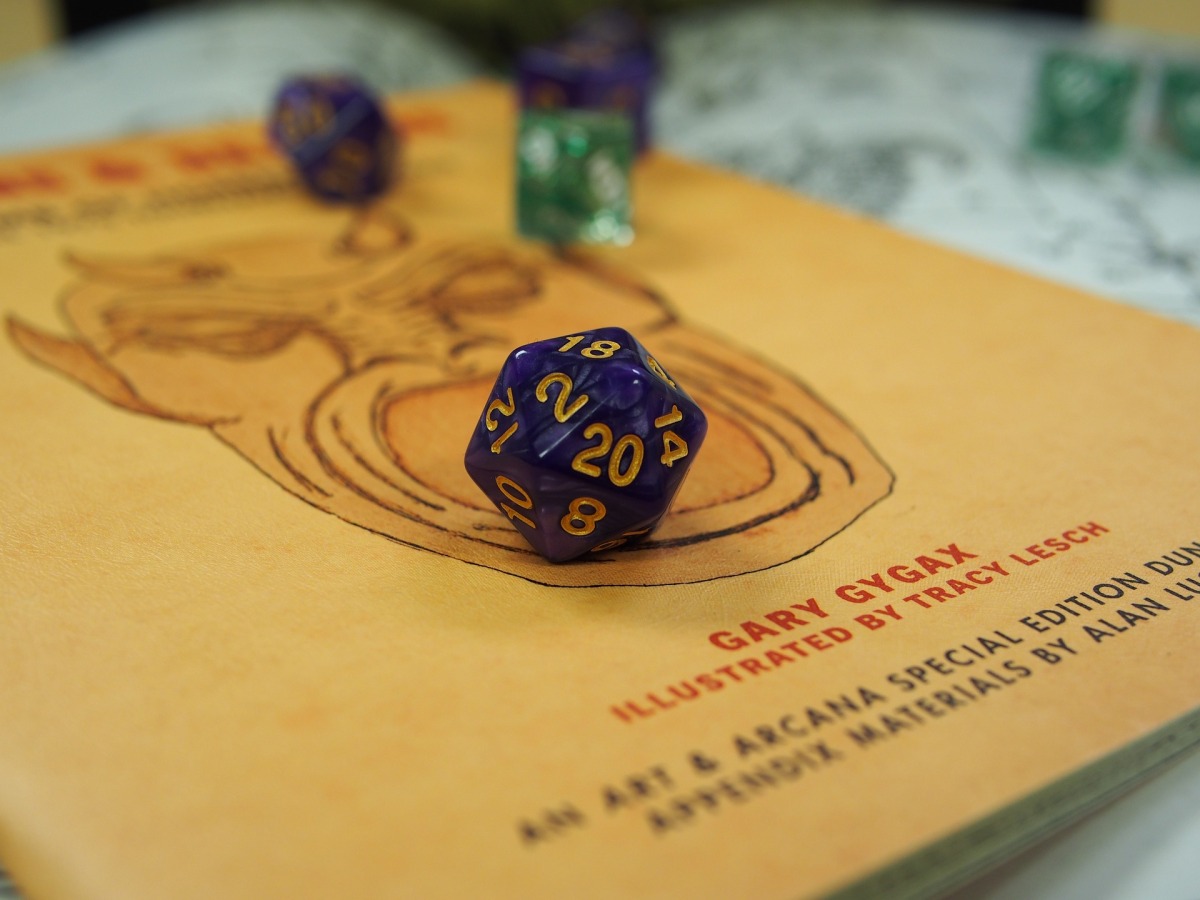

While it is always worthwhile being aware of the available documentation, there are many self-proclaimed “experts” out there, and much conflicting advice. Some classic texts, e.g. The C Programming Language by Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie or Baby and Child Care by Dr Benjamin Spock, are generally considered outdated in some circles, while yet others may lead to theological arguments. Some older non-core contributors (see, for example, “mothers-in-law”, above), may have particular attachments to approaches which are not considered “safe” in modern software or child development.

6. Maintenance

While the initial creation step is generally considered the most enjoyable in both software and child development processes, the vast majority of the development lifecycle revolves around maintenance. Keeping your project or child secure, resilient and operational or enabling them to scale outside the confines of the originally expected environment, where they come into contact with other projects, can quickly become a full-time job. Many contributors, at this point, will consider outside help to manage these complexities.

7. Scope creep

Software projects don’t always go in the direction you intend (or would like), discovering a mind of their own as they come into contact with external forces and interacting in contexts which are not considered appropriate by the original creators. Once a project reaches this stage, however, there is little that can be done, and community popularity – considered by most contributors as a positive attribute at earlier stages of lifecycle – can lead to some unexpected and possibly negative impacts on the focus of the project as competing interests vie to influence the project’s direction. Careful management of resources (see below) is the traditionally approach to dealing with this issue, but can backfire (withdrawal of privileges can have unexpected side effects in both software and human contexts).

8. Resource management

Any software project always expands to available resources. The same goes for children. In both cases, in fact, there will always appear to be insufficient resources to meet the “needs” of the project/child. Be strong. Don’t give in. Consider your other projects and how they could flourish if provided with sufficient resources. Not to mention your relationships with other contributors. And your own health/sanity.

9. Hand-over

At some point, it becomes time to hand over your project. Whether this is to new lead maintainer (or multiple maintainers – we should be open-minded), to an academic, government or commercial institution, letting go can be difficult. But you have to let go. Software projects – and children – can rarely grow and fulfil their potential under the control of the initial creators. When you do manage to let go, it can be a liberating experience for you and your creation. Just don’t expect that you’ll be entirely free of them: for some reason, as the initial creator, you may well be expected to arrange continued resources well past the time you were expecting. Be generous, and enjoy the nostalgia, but you’re not in charge, so don’t expect the resources to be applied as you might prefer.

Conclusion

I’m aware that there are times when children – and even software projects – can actually cause pain and hurt, and I don’t want to minimise the negative impact that the inability to have children, their illness, injury or loss can have on individuals and families. Please accept this light-hearted offering in the spirit it is meant, and if you are negatively affected by this article, please consider accessing help and external support.