Mike Bursell

Sponsored by Super Protocol

Introduction

One of the things that I enjoy the most is taking two different technologies, accelerating them at speed and seeing what comes out when they hit, rather in the style of a particle physicist with a Large Hadron Collider. Technologies which may not seem to be obvious fits for each other, when combined, sometimes yield fascinating – and commercially exciting – results, and the idea of putting Web3 and Confidential Computing together is certainly one of those occasions. Like most great ideas, once someone explained it to me, it was a “oh, well, of course that’s going to make sense!” moment, and I’m hoping that this article, which attempts to explain the combination of the two technologies, will give you the same reaction. I’ll start with an introduction to the two technologies separately, why they are interesting from a business context, and then look at what happens when you put them together. We’ll finish with more of a description of a particular implementation: that of Super Protocol, using the Polygon blockchain.

Business context

Introduction to the technologies

In this section, we look at blockchain in general and Web3 in particular, followed by a description of the key aspects of Confidential Computing. If you’re already an expert in either of these technologies, feel free to skip these, of course.

Blockchain

Blockchains offer a way for groups of people to agree about the truth of key aspects of the world. They let people say: “the information that is part of that blockchain is locked in, and we – the other people who use it and I – believe that is correct and represents a true version of certain facts.” This is a powerful capability, but how does it arise? The key point about a blockchain is that it is immutable. More specifically, anything that is placed on the blockchain can’t be changed without such a change being obvious to anybody with access to it. And another key point about many blockchains is that they are public – that is, anybody with access to the Internet and the relevant software is able to access them. Such blockchains are sometimes called “permissionless”, in juxtaposition to blockchains to which only authorised entities have access, which are known as “permissioned”. In both cases, the act of putting something on a blockchain is very important – if we want to view blockchains as providing a source of truth about the world – then the ability to put something onto the blockchain is a power that comes with great responsibility. The various consensus mechanisms employed vary between implementations but all of them aim for consensus among the parties that are placing their trust in the blockchain, a consensus that what is being represented is correct and valid. Once such a consensus has been met a cryptographic hash is used to seal the latest information and anchor it to previous parts of the blockchain, adding a new block to it.

While this provides enough for some use cases, the addition of smart contracts provides a new dimension of capabilities. I’ve noted before that smart contracts aren’t very well named (they’re arguably neither smart nor contracts!), but what they basically allow is for programs and their results to be put on a blockchain. If I create a smart contract and there’s consensus that it allows deterministic results from known inputs, and it’s put onto the blockchain, then that means that when it’s run, if people can see the inputs – and be assured that the contract was run correctly, a point to which we’ll be returning later in this article – then they will happy to put the results of that smart contract on the blockchain. What we’ve just created is a way to create data that is known to be correct and valid, and which we can be happy to put directly on the blockchain without further checking: the blockchain can basically add results to itself!

Web3

Blockchains and smart contracts, on their own, are little more than a diverting combination of cryptography and computing: it’s the use cases that make things interesting. The first use case that everyone thinks of is crypto-currency, the use of blockchains to create wholly electronic currencies that can be (but don’t have) divorced from centralised government-backed banking systems. (Parenthetically, the fact that the field of use and study of these crypto-currencies has become known to its enthusiasts as “crypto” drives most experts in the much older and more academic field of cryptology wild.)

There are other uses of blockchains and smart contracts, however, and the one which occupies our attention here is Web3. I’m old (I’m not going to give a precise age, but let’s say early-to-mid Gen X, shall we?), so I cut my professional teeth on the technologies that make up what are now known as Web1. Web1 was the world of people running their own websites with fairly simple static pages and CGI interactions with online databases. Web2 came next and revolves around centralised platforms – often cloud-based – and user-generated data, typically processed and manipulated by large organisations. While data and information may be generated by users, it’s typically sucked into the platforms owned by these large organisations (banks, social media companies, governments, etc.), and passes almost entirely out of user control. Web3 is the next iteration, and the big change is that it’s a move to decentralised services, transparency and user control of data. Web3 is about open protocols – data and information isn’t owned by those processing it: Web3 provides a language of communication and says “let’s start here”. And Web3 would be impossible without the use of blockchains and smart contracts.

Confidential Computing

Confidential Computing is a set of technologies that arose in the mid 2010s, originally to address a number of the problems that people started to realise were associated with cloud computing and Web2. As organisations moved their applications to the cloud, it followed that the data they were processing also moved there, and this caused issues. It’s probably safe to say that the first concerns that surfaced were around the organisations’ own data. Keeping financial data, intellectual property, cryptographic keys and the like safe from prying eyes on servers operated in clouds owned and managed by completely different companies, sometimes in completely different jurisdictions, started to become a worry. But that worry was compounded by the rising tide of regulation being enacted to protect the data not of the organisations, but of the customers who they (supposedly) served. This, and the growing reputational damage associated with the loss of private data, required technologies that would allow the safeguarding of sensitive data and applications from the cloud service providers and, in some cases, from the organisations who “owned” – or at least processed – that data themselves.

Confidential Computing requires two main elements. The first is a hardware-based Trusted Execution Environment (TEE): a set of capabilities on a chip (typically a CPU or GPU at this point) that can isolate applications and their data from the rest of the system running them, including administrators, the operating system and even the lowest levels of the computer, the kernel itself. Even someone with physical access to the machine cannot overcome the protection that a TEE provides, except in truly exceptional circumstances. The second element is remote attestation. It’s all very well setting up a TEE on a system in, say, a public cloud, but how can you know that it’s actually in place or even that the application you wanted to load into it is the one that’s actually running? Remote attestation addresses this problem in a multi-step process. There are a number of ways to manage this, but the basic idea is that the application in the TEE asks the CPU (which understands how this works) to create a measurement of some or all of the memory in the TEE. The CPU does this, and signs this with a cryptographic key, creating an attestation measurement. This measurement is then passed to a different system (hence “remote”), which checks it to see if it conforms to the expectations of the party (or parties) running the application and, if it does, provides a verification confirms that all is well. This basically allows a certificate to be created that attests to the correctness of the CPU, the validity of the TEE’s configuration and the state of any applications or data within the TEE.

With these elements – TEEs and remote attestation – in place, organisations can use Confidential Computing to prove to themselves, their regulators and their customers that no unauthorised peeking or tampering is possible with those sensitive applications and data that need to be protected.

Combining blockchain & CC

One thing – possibly the key thing – about Web3 is that it’s decentralised. That means that anyone can offer to provide services and, most importantly, computing services, to anybody else. This means that you don’t need to go to one of the big (and expensive) cloud service providers to run your application – you can run a DApp (Decentralised Application) – or a standard application such as a simple container image – on the hardware of anyone willing to host it. The question, of course, is whether you can trust them with your application and your data; and the answer, of course in many, if not most, use cases, is “no”. Cloud service providers may not be entirely worthy of organisations’ trust – hence the need for Confidential Computing – but at least they are publicly identifiable, have reputations and are both shameable and suable. It’s very difficult to say the same about in a Web3 world about a provider of computing resources who may be anonymous or pseudonymous and with whom you have never had any interactions before – nor are likely to have any in the future. And while there is sometimes scepticism about whether independent actors can create complex computational infrastructure, we only need look at the example of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency miners, who have built computational resources which rival those of even the largest cloud providers.

Luckily for Web3, it turns out that Confidential Computing, while designed primarily for Web2, has just the properties needed to allow us to build systems that do allow us to do Web3 computing with confidence (I’ll walk through some of the key elements of one such implementation – by Super Protocol – below). TEEs allow DApps to be isolated from the underlying hardware and system software and remote attestation can provide assurances to clients that everything has been set up correctly (and a number of other properties besides).

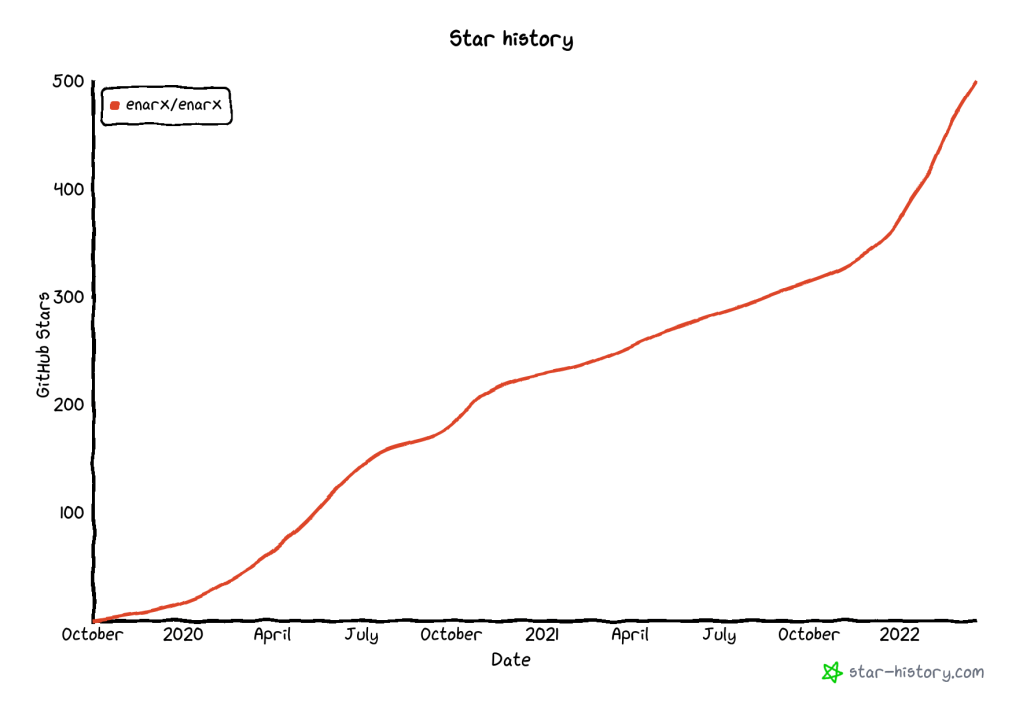

Open source

There is one important characteristic that Web3 and Confidential Computing share that is required to ensure the security and transparency that is a key to a system that combines them: open source software. Where software is proprietary and closed from scrutiny (this is the closed from which open source is differentiated), the development of trust in the various components and how they interact is impossible. Where proprietary software might allow trust in a closed system of actors and clients who already have trust with each other – or external mechanisms to establish it – the same is not true in a system such as Web3 whose very decentralised nature doesn’t allow for such centralised authorities.

Open source software is not automatically or by its very nature more secure than proprietary software – it is written by humans, after all (for now!), and – but its openness and availability to scrutiny means that experts can examine it, check it and, where necessary, fix it. This allows the open source community and those that interact with it to establish that it is worthy of trust in particular contexts and use cases (see Chapter 9: Open Source and Trust in my book for more details of how this can work). Confidential Computing – using TEEs and remote attestation – can provide cryptographic assurances not only the elements of a Web3 system are valid and have appropriate security properties, but also that the components of the TEE itself do as well.

Some readers may have noted the apparent circularity in this set-up – there are actually two trust relationships that are required for Confidential Computing to work: in the chip manufacturer and in the attestation verification service. The first of these is unavoidable with current systems, while the other can be managed in part by performing the attestation oneself. It turns out that allowing the creation of trust relationships between mutually un-trusting parties is extremely complex, but one way that this can be done is what we will now address.

Super Protocol’s approach

Super Protocol have created a system which uses Confidential Computing to allow execution of complex applications to be made within a smart contract on the blockchain and for all the parties in the transaction to have appropriate trust in the performance and result of that execution without having to know or trust each other. The key layers are:

- Client Infrastructure, allowing a client to interact with the blockchain, initiate an instance and interact with it

- Blockchain, including smart contracts

- Various providers (TEE, Data, Solution, Storage).

Central to Super Protocol’s approach are two aspects of the system: that it is open source, and that remote attestation is required to allow the client to have sufficient assurance of the system’s security. Smart contracts – themselves open source – allow the resources made available by the various actors and combined into an offer that is placed on the blockchain and is available to anyone with access to the blockchain – to execute it, given sufficient resources from all involved. What makes this approach a Web3 approach, and differentiates it from a more Web2 system, is that none of these actors needs to be connected contractually.

Benefits of This Approach

How does this approach help? Well, you don’t need to store or process data (which may be sensitive or just very large) locally: TEEs can handle it, providing confidentiality and integrity assurances that would otherwise be impossible. And communications between the various applications are also encrypted transparently, reducing or removing risks of data leakage and exposure, without requiring complex key management by users, but keeping the flexibility and exposure offered by decentralisation and Confidential Computing.

But the step change that this opens up is the network effect enabled by the possibility of building huge numbers of interconnected Web3 agents and applications, operating with the benefits of integrity and confidentiality offered by Confidential Computing, and backed up by remote attestation. One of the recurring criticisms of Web2 ecosystems is their fragility and lack of flexibility (not to mention the problems of securing them in the first place): here we have an opportunity to create complex, flexible and robust ecosystems where decentralised agents and applications can collaborate, with privacy controls designed in and clearly defined security assurances and policies.

Technical details

In this section, I dig a little further into some of the technical details of Super Protocol’s system. It is, of course, not the only approach to combining Confidential Computing and Web3, but it is available right now, seems carefully architected and designed with security foremost in mind and provides a good example of the technologies and the complexities involved.

You can think of Super Protocol’s service as being in two main parts: on-chain and off-chain. The marketplace, with smart contract offers, sits on an Ethereum blockchain, and the client interacts with that, never needing to know the details of how and where their application instance is running. The actual running applications are off-chain, supported by other infrastructure to allow initial configuration and then communication services between clients and running applications. The “bridge” between the two parts, which moves from an offer to an actual running instance of the application, is a component called a Trusted Loader, which sets up the various parts of the application and sets it running. The data it is managing contains sensitive information such as cryptographic keys which need to be protected as they provide security for all the other parts of the system and the Trusted Loader also manages the important actions of hash verification (ensuring that what is being loaded what was originally offered) and order integrity (ensuring that no changes can be made whilst the loading is taking place and execution starting).

But what is actually running? The answer is that the unit of execution for an application in this service is a Kubernetes Pod, so each application is basically a container image which is run within a Pod, which itself executes within a TEE, isolating it from any unauthorised access. This Pod itself is – of course! – measured, creating an attestation measurement that can now be verified by clients of the application. We should also remember that the application itself – the container image – needs protection as well. This is part of the job of the Trusted Loader, as the container image is stored encrypted, and the Trusted Loader has appropriate keys to decrypt this and other resources required to allow execution. This is not the only thing that the Trusted Loader does: it also gathers and sets up resources from the smart contract for networking and storage, putting everything together, setting it running and connecting the client to the running instance.

There isn’t space in this article to go into deeper detail of how the system works, but by combining the capabilities offered by Confidential Computing and a system of cryptographic keys and certificates, the overall system enforces a variety of properties that are vital for sensitive, distributed and decentralised Web3 applications.

- Decentralised storage: secrets are kept in multiple places instead of one, making them harder to access, steal or leak.

- Developer independence: creators of applications can’t access these secrets, continuing the lack of need for trust relationships between the various actors. In other words, each instance of an application is isolated from its creator, maintaining data confidentiality.

- Unique secrets: Each application gets its own unique secrets that nobody else can use or see and which are not shared between instances.

Thanks

Thanks to Super Protocol for sponsoring this article. Although they made suggestions and provided assistance around the technical details, this article represents my views, the text is mine and final editorial control (and with it the blame for any mistakes!) rests with the author.

Photo by Rukma Pratista on Unsplash